This is part two of a multi-part series. Check out part one if you haven’t already, then check out part three next!

Hello and welcome back! We’re going to pick up right where we left off. In Redeployment Part One, we emerged from polar night, deep-cleaned the station, and prepared for the first flight and the arrival of our summer crew.

First Flight

The first flight of the season isn’t actually destined for the South Pole. It’s a “mobilization” or “transit” flight, and the South Pole is just a convenient stop along their route!

During the Antarctic summer, Kenn Borek Air (KBA) flies all over Antarctica, under contract with the United States Antarctic Program and several other national Antarctic programs. But these planes don’t stay in Antarctica year-round – they “de-mobilize” and fly back to Canada at the end of the Antarctic summer.

Before these planes and their flight crews can start doing on-continent flights across Antarctica, they have to get to Antarctica once again. For example, the planes that will fly missions for the United States Antarctic Program need to get all the way from Canada to their summer base of operations at McMurdo.

For smaller planes (KBA Baslers and Twin Otters), it’s simply not feasible to fly the same route as larger intercontinental planes. The intercontinental route takes these larger planes around the non-Antarctic world, through Christchurch, and across the South Pacific Ocean and Southern Ocean to McMurdo. For smaller planes, the distances involved are just too great. Even with ferry tanks, it’s too far for these planes to fly safely. The distance from Christchurch to McMurdo is about 2,415 miles.

Instead, these KBA planes depart Canada and travel down through North and South America, making whatever stops are necessary along the way. The planes arrive and hold in Punta Arenas, Chile. Punta Arenas is one of the main Antarctic gateway cities for operations on the Antarctic Peninsula.

Once a good weather window opens up, they fly across the Drake Passage to Rothera, a British Antarctic Survey (BAS) station on the Antarctic Peninsula. Rothera is located about 1,013 miles from Punta Arenas.

Here’s a quick timelapse that shows runway operations at Rothera, courtesy of Matt Hughes from BAS (Instagram, X/Twitter) and included here with Matt’s permission:

Once the planes arrive at Rothera, they need to get all the way to McMurdo, on the opposite coast of Antarctica. The shortest route takes them through the South Pole! For this particular transit path, Pole is just a glorified pit stop. Pole is located about 1,550 miles from Rothera, and McMurdo is located about 845 miles from Pole.

The planes will depart Rothera when there’s a good weather window. Once a plane arrives at the South Pole, if it’s a Basler, the crew will usually want fuel and a quick stretch, then they’re on their way. If it’s a smaller / slower plane such as a Twin Otter, they may stay overnight. This depends on how long they’ve been flying and where they are heading.

This means that, for Baslers transiting through Pole to McMurdo, a “good weather window” means good weather at Rothera and Pole and McMurdo, all on the same day. This is necessary to minimize the likelihood of the crew having to stay the night at Pole.

Rothera is much better equipped for overnight guests than Pole, for both the crew and the plane itself. Although, when necessary, Pole does have the infrastructure to support planes on the ground for extended periods of time.

Our first flight was a Basler, mobilizing through Pole en route to its final destination. It arrived from Rothera on the morning of October 24, 2023. This was the first outside human contact for winterover Polies since February 2023!

Photo is again courtesy of fellow winterover Jeff Capps (Instagram):

The plane didn’t stay on the ground long. Just long enough to say hello, fill up on fuel, and drop off some unofficial but MUCH-appreciated cargo: Freshies.

This wasn’t an official USAP resupply flight to Pole, but the flight crew was kind enough to carry a small amount of fresh foods for the overwintering crew at Pole. We hadn’t seen fresh food in several months, so even a small amount (we’re talking one piece of fruit per Polie) was a fantastic gift.

Station Opening

After the first mobilization flight, it was only a few more days until the next major milestone: Station Opening!

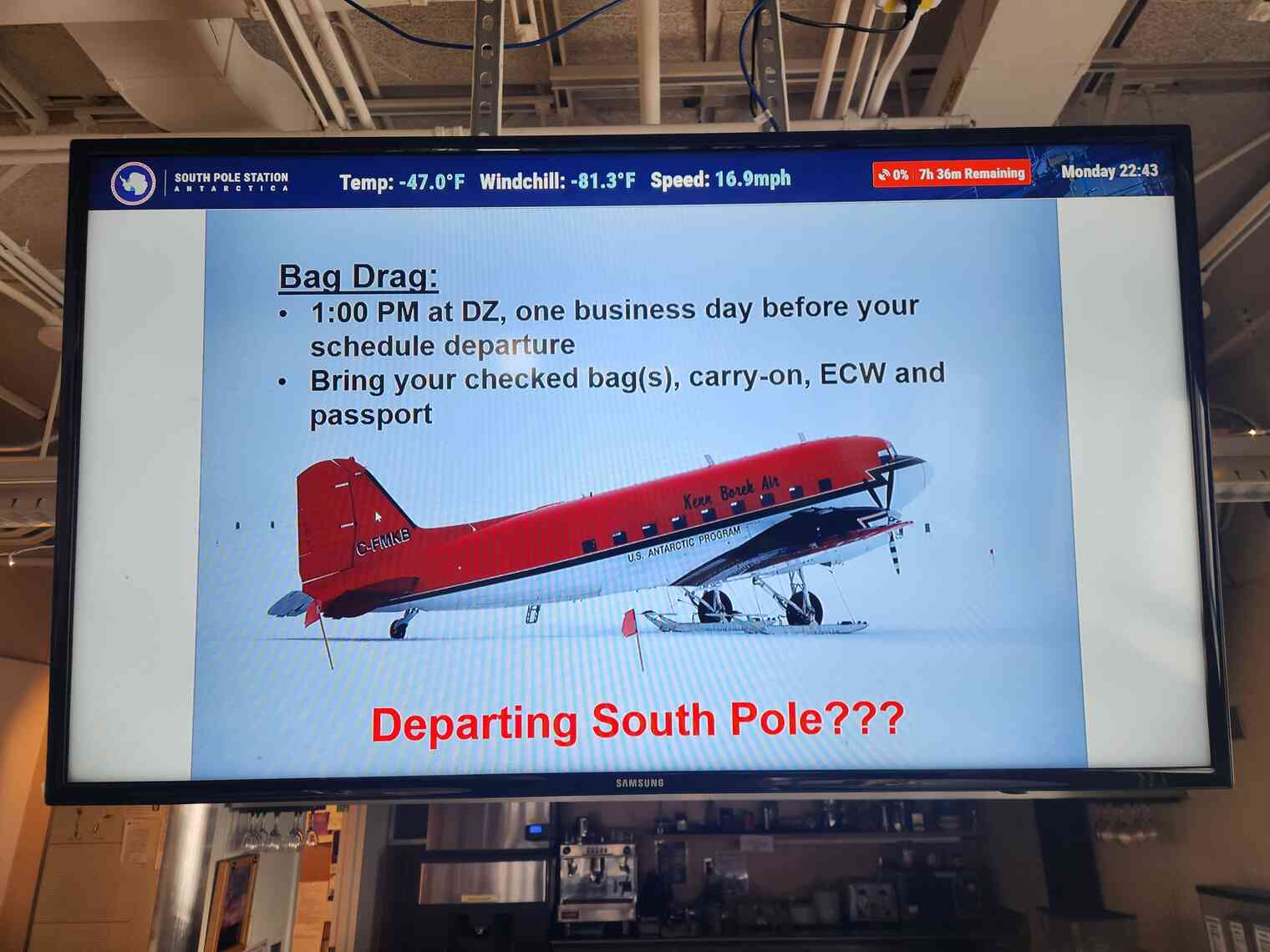

It began to feel “real” once we put the flight slide back up on our slideshow. We turn this one off over the winter – with no flights for 8.5 months, it’s not necessary. There’s no sense in teasing us all winter with abstract concepts such as “departing South Pole”. Turning it back on, a week before station opened, served as a reminder that things were about to feel much different vs. this isolated winter we had grown used to.

On Saturday, October 28, 2023, we welcomed our first official USAP inbound/outbound passenger flight between McMurdo and South Pole. This was on one of the Baslers that had mobilized through Pole just a few days prior.

The first flight always brings in the “adults” – the fulltime staff who work on the Antarctic program year-round. Most of them deploy for the summer, then leave for the winter, leaving the station under the care of seasonal contractors (like me!).

This rotation (summer at Pole, winter remote) allows the fulltimers to oversee summer station projects, but it also gives them enough time offsite during the Antarctic winter. These are more “career” positions, vs. the “seasonal contractor” positions that make up the majority of the support staff. The expectation is that this is a stable, sustainable pace of work that allows the fulltimers to remain in their positions year-after-year. Summer at Pole for these folks is usually between 3 and 3.5 months.

Of course, the first flight also brought our first official resupply of freshies!

This first resupply also included eggs! Our first in almost 5 months, since we consumed The Last Egg of the winter on June 6, 2023.

The freshies were, of course, rationed carefully. This ensured that us crusty winterovers had our fill. This is mostly a playful thing on station, but there’s truth to the sentiment.

If you’ve just arrived on station, that means you’ve come from Real Life™, where you recently had access to all the fresh food you can eat. By contrast, us winterovers are at the tail end of 8.5 months of isolation. We haven’t tasted fresh food in a long time. Please – leave the eggs for us. We need them.

With the first flight, we also begin saying goodbye to our first round of winterover colleagues. Many of us met for the first time at Pole, and we spent 8.5+ months isolated together.

Pole quickly became our entire lives, for better or worse. It was a static and fixed population, and after months of immersion, it began to feel eternal and unchanging. The outside world feels less… real when you’re at Pole. You’re separated by physical and information barriers. You can’t go anywhere, and your access to the world is exclusively through slow and unreliable Internet connectivity.

When we said goodbye to some of our colleagues, it was the first real milestone that surfaced long-repressed feelings about “real life”, the transient nature of contract work, and the prospect of reintegrating into society. Our colleagues were leaving. They were going to get out of Antarctica. There is a real world beyond this place, and in just a few short days, they would be back in it.

The flight out of Pole can’t carry as many people as the flight into Pole. When the plane departs McMurdo, it’s taking off from sea level. When the plane departs Pole, it’s taking off from almost 10,000 feet above sea level. The allowable cargo load is lower for this takeoff from elevation. A Basler can typically carry 11-14 people to Pole and 6-8 people out of Pole, depending on passenger weight and cargo requirements.

Turnover and Eternal Waiting

Station opening marked the beginning of the turnover phase of Antarctic life. Newcomers arrived on every subsequent flight, and winterovers began trickling out. Choosing who flies in and who flies out is a delicate balance, and it changes day-to-day.

Some teams need more time to hand off their work, from the outgoing winterovers to the incoming summer staff. Some teams need less. Some teams have a lot of work that happens all at once, and the winterovers have to stay longer to help.

Some teams can’t even begin turnover until critical support roles are filled and summer teams are up and running. Summer replacements for those teams typically won’t make it down until the required support staff are in place. This means those winterovers are stuck at Pole the longest, long after their fellow winterover colleagues have departed.

In addition, we’re limited by flight capacity. For the first several weeks of the summer season, we only have Baslers. The LC-130s need more support infrastructure (for example, firefighting teams) on the ground at Pole. The infrastructure to support LC-130s can only be built out once the first critical summer staff have arrived on Baslers.

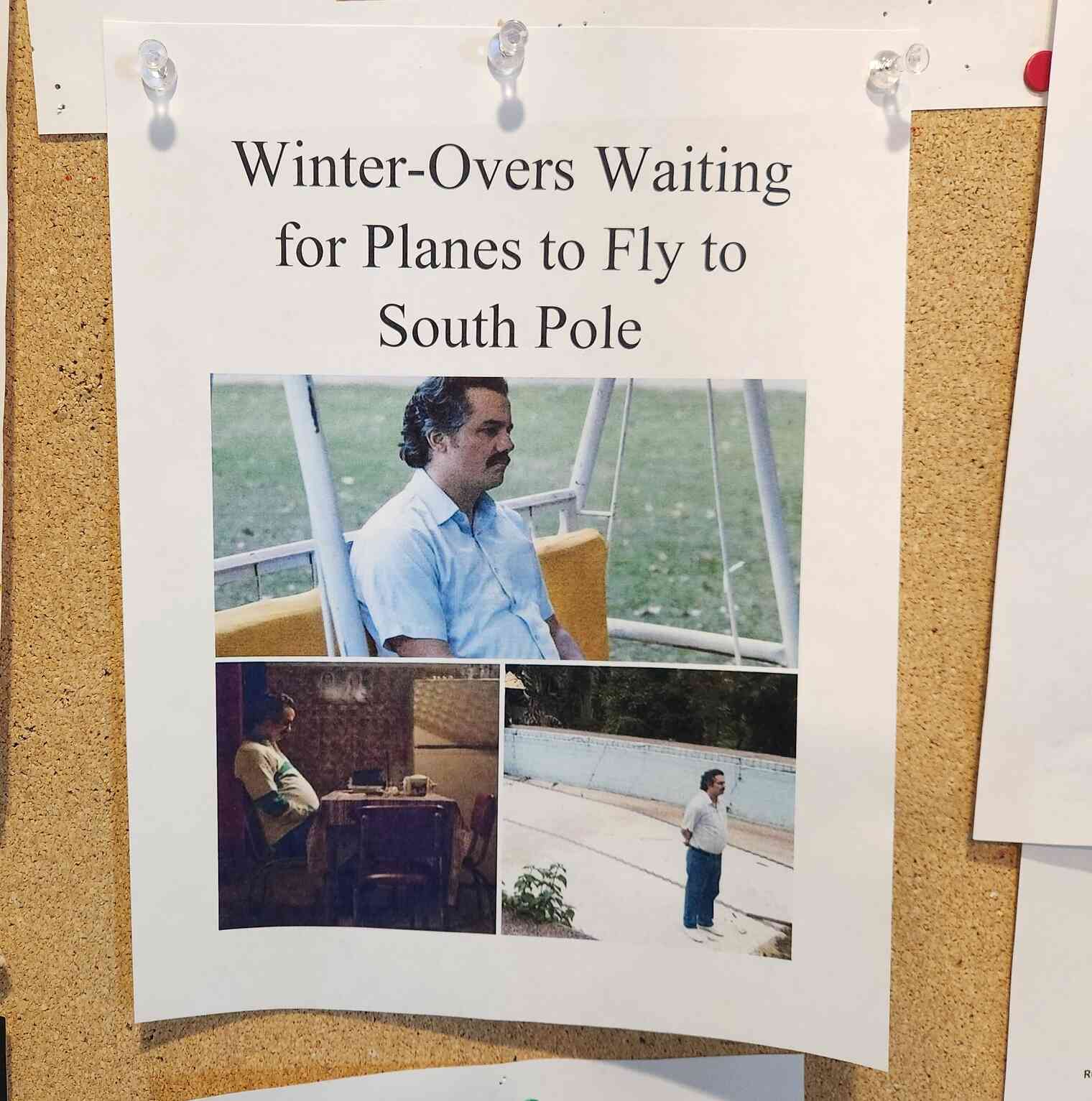

Baslers can hold only a handful of people, and the weather is always dicey this time of year. This means lots of canceled flights! In the 18 days between when the first flight arrived and when I finally flew out, we only managed to get five total flights to Pole, despite trying nearly every single day. Weather, equipment, and personnel issues contributed to a series of delays. These delays are typical, but they’re still frustrating for antsy winterovers who want to get out at the end of a long winter.

The majority of winterovers do not stay the upcoming summer. Some folks do summer and then winter, but very few do winter and then summer. It’s easy to go from fast-paced, bustling summer into relaxing, slow winter. It’s much harder to go the other direction, from winter into summer. By the end of winter, most of us, however well-adjusted, however strong our coping mechanisms, were ready to get out of there.

Everyone has their own superstition or ritual for cutting through the delays and summoning a plane. It’s a silly notion, but it’s something to do. It provides a much-needed distraction from the stress of waiting, and it lets us dream that we’re somehow in control of the weather.

For some, it’s a special meal. “If galley makes Chicken and Dumplings, the plane will come.”

For others, it’s drinking alcohol. “If I am hungover and don’t want to move, the plane will come and I’ll have to drag myself onto it.”

For others, it’s a movie. We chose Shrek. If we watch Shrek, the plane will come. We watched Shrek SEVERAL times. Nobody said the ritual was guaranteed to succeed.

Eternal waiting also meant going over and over in your head, trying to figure out what else you should see while you’re still at Pole. Most of us had been here about a year, and we’ve seen everything.

We all lived, for an entire winter, just a few hundred feet from the actual, geographic South Pole. Literally any time I wanted to, I could go outside and touch it. It was easy! It was right there! Only ~1,700 people, in the history of forever, have ever had the experience of wintering over at the South Pole. It was 100°F below zero! It was pitch black! We were doing world-changing science! We were thousands of miles from civilization!

Most of us were very much over it. We were desensitized to the sheer mind-boggling novelty of where we were. We went about our daily routines, and the unique context faded into the background. We sat around in our pajamas, sipping tea, playing board games. The most interesting topic of conversation is whether there would be tater tots at breakfast tomorrow.

But in these last few days, I did my best to recapture the magic of where I was. I walked around station, inside and out. I paid attention to the little details and the unique things I could only do here.

For example, here’s a quick walk around the geographic South Pole, in which I hit every longitudinal value over the course of 37 seconds. Anyone could do this! At any time! For a brief few minutes, I was the World’s Southernmost Human. I did this once when I arrived, once or twice throughout the year, and now, just days before I departed, I was doing it for the last time.

Side note: My walk around the world was only 37 seconds, because I was so close to the convergence point. Polar sailing events in the Southern Ocean also have to contend with this same issue. The tighter your route, i.e. the further South you are, the faster you can complete the circumnavigation. Here’s a fascinating article explaining how the organizers of a polar sailing event established an Ice Exclusion Zone. Obviously sailors would have an incentive to go as far South as possible to shorten the course, but that increases the risk of hazardous encounters with icebergs. Hence, a southern limit for the event.

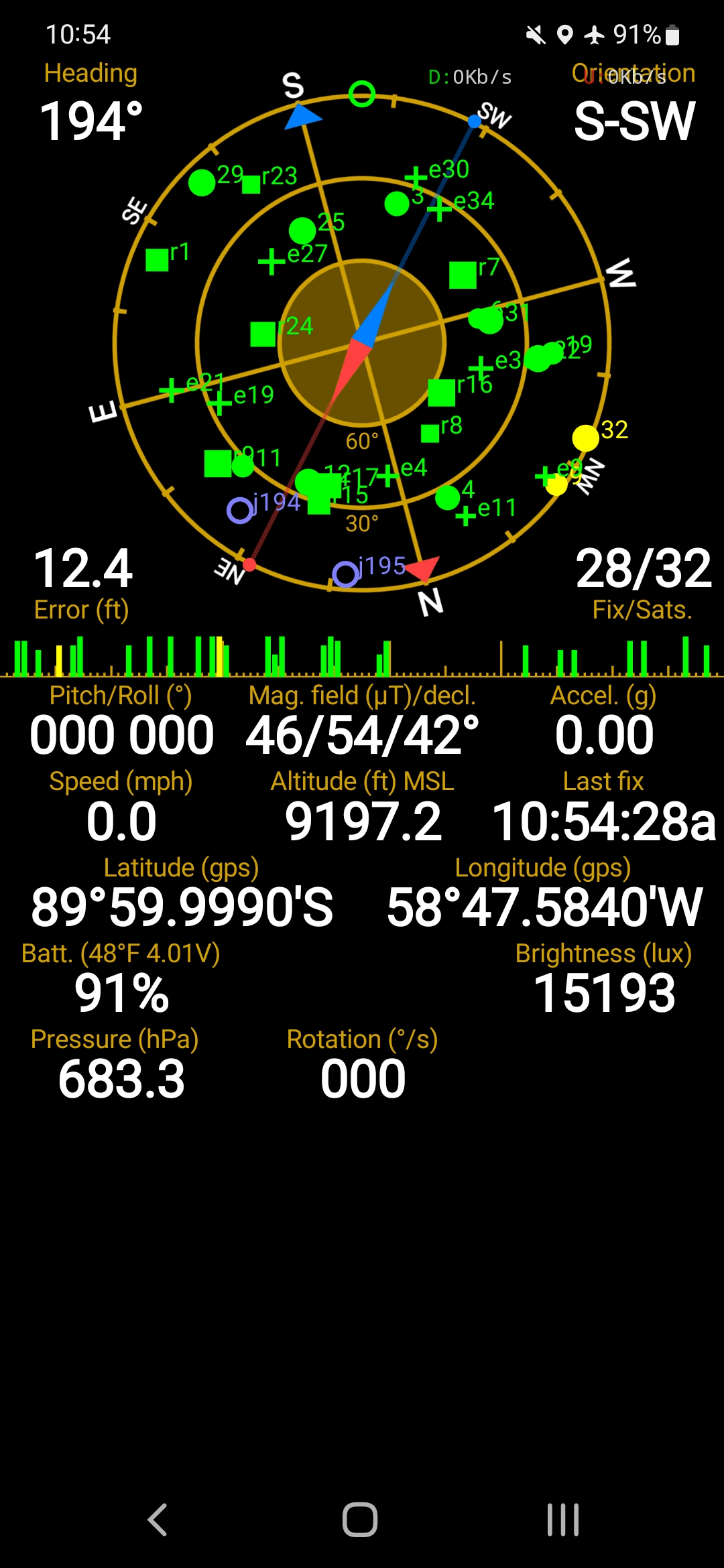

Speaking of the geographic South Pole – here’s my attempt from last Summer to get as close to the geographic South Pole as my phone’s GPS would register.

This was shortly after I arrived at Pole, during Summer 2022/2023. I remember being thrilled and geeking out about the sheer novelty of standing at the bottom of the world.

I was able to get to 89°59.9990’S latitude! I’m not sure if this is a limitation of the Android GPS infrastructure, a limitation in this particular GPS app, or if I simply wasn’t persistent enough to find exactly 90°00.0000’S.

If I had been able to find 90°00.0000’S exactly, the displayed compass would have been inaccurate. There is no South, East, or West from exactly 90°S, only North in every direction! A fun edge case for compass design. You can see what this would look like in this stylized representation from the 2014 pole marker. This photo is from SouthPoleStation.com.

South Pole Departure

My scheduled flight out of Pole was the first LC-130. After four Baslers, we finally had the ground crew on hand, and the LC-130s had made it “on-continent” from Christchurch. My flight would be the first passenger/cargo LC-130 between McMurdo and Pole.

On the morning of November 16, 2023, Comms greeted us with the radio call we were all hoping for:

Attention South Pole, attention South Pole: Skiier <number> has departed Williams field, and is estimating South Pole at 1430. This is an inbound / outbound passenger flight. Thank you.

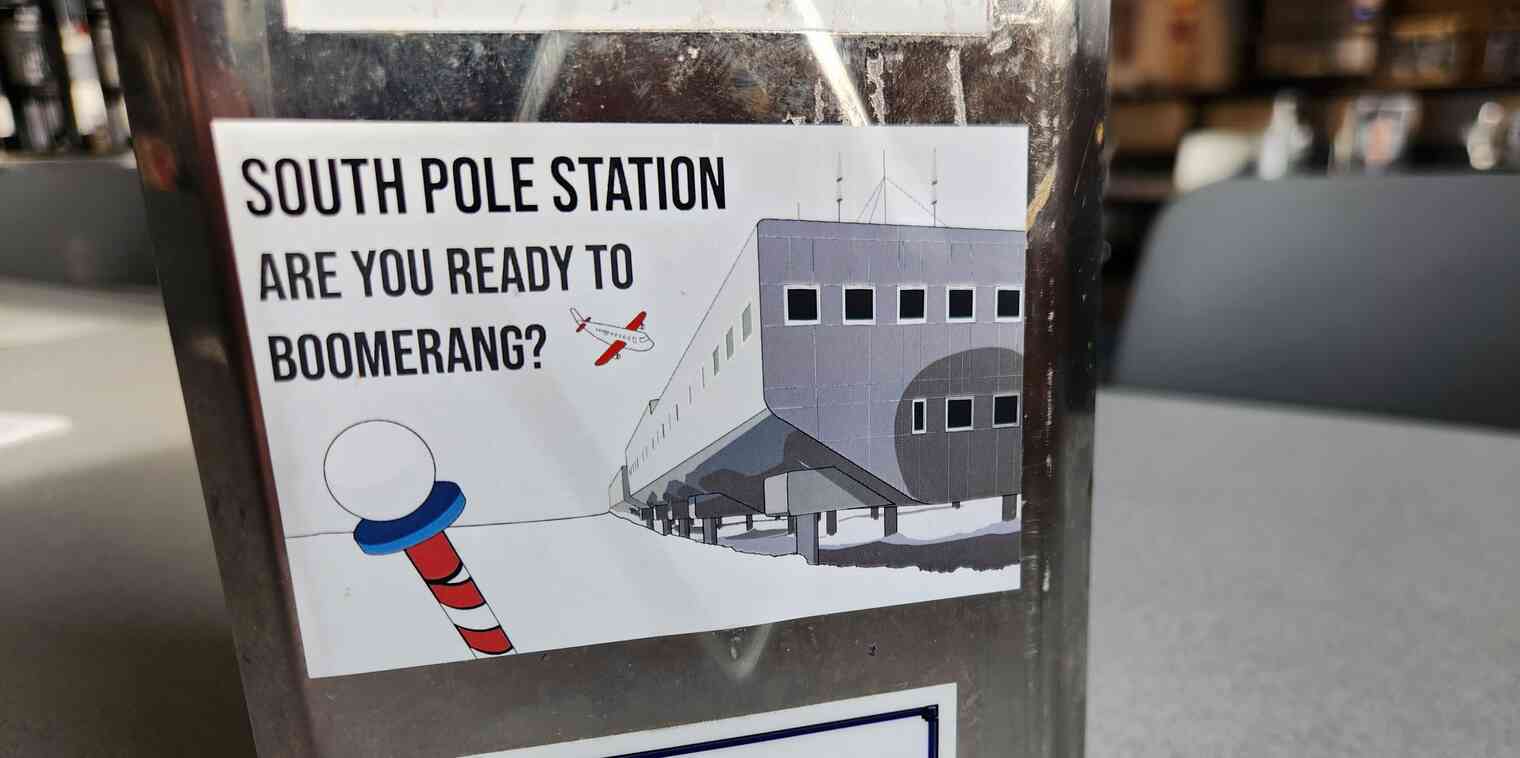

The plane was heading our way! Now the final remaining risk was a “boomerang”. A boomerang is when the plane turns around mid-flight due to weather or mechanical issues.

A boomerang is emotional whiplash for the affected Antarcticans, coming or going. If you were bright-eyed, full of energy, and excited to get to Pole? Sorry. If you were crusty, worn out after a long winter, and ready to get back to civilization? Sorry.

Once the flight passed “Pole 3”, an in-flight landmark most of the way to Pole, the fear of a boomerang faded. The plane was almost guaranteed to make it all the way. This was when it became real: we were actually, truly leaving!

In the last few minutes before the plane landed, we did a final walkthrough of our rooms, making sure they were clean and ready for the next crew. I had lived here for 11 months, and now it was cleaned out and ready for a new arrival:

When the plane landed, the new arrivals shuffled into the station. There were quite a few of them! LC-130s are large, and they can carry a lot of passengers and cargo. These are our workhorse planes. Pole will get several LC-130s per week throughout the summer.

Cargo staff began unloading pallets of cargo for Pole, and loading pallets of cargo destined for McMurdo.

The last order of business for departing passengers inside the station was to drop off our radios, so they could be reprogrammed for the new summer staff.

Finally, our little group of departing winterovers, myself included, left South Pole Station for the season.

As we walked to the plane, we all stopped to take a final round of photos and videos. It was an exciting moment! We were thrilled that we were finally leaving, but we were also aware that many of us would choose not to return for a subsequent season. Our last few minutes at the South Pole!

And then, suddenly, we were on the plane and departing Pole. It’s the same type of plane I flew in on – see South Pole Arrival for more photos.

Once we were in the air, we alternated between relaxing and staring out the windows. Once we got closer to the coast, we began to see mountains for the first time since arriving at Pole. Pole is completely featureless – no mountains, no rocks, no dirt whatsoever. Just flat, miles-thick ice as far as the eye can see. Seeing mountains out the window was a treat.

This is part two of a multi-part series. Check out part one if you haven’t already, then check out part three next!