South Pole Station sits on the polar plateau, a mostly-featureless expanse of snow and ice, several miles thick, extending as far as the eye can see in all directions. Onto this stark, barren landscape, we’ve established a series of stations throughout the decades.

They’ve varied in size, style, complexity, comfort, and prestige. From Old Pole, to the Dome, to the modern Elevated Station, the United States has maintained some type of presence at the South Pole continuously for a long time.

One thing all these stations have in common? Nature is constantly trying to bury them! And it’s succeeding.

I’ll include the obligatory preface here. I am an IT worker. My skills and knowledge are in computers, not snowdrift modeling. I have suddenly found myself in a strange, unfamiliar place, beyond my comprehension. This place is full of wonderful new infrastructure and infrastructure-adjacent features.

I have also, to my surprise, stumbled my way into running a somewhat popular Antarctica blog. Hello Internet People!

Everything I say here is based on me just walking around, photographing things, and making some (hopefully!) safe inferences about how this place works. There are professionals, both here and elsewhere, who devote their entire careers to modeling and compensating for snowdrift! Listen to them, not me, if you want to learn more about this stuff. I am far outside my element here.

Now without further ado – here’s some observations on the topography of South Pole Station.

Since every direction is technically “North” from here, we use a grid overlay, to bring some semblance of order to our surroundings. The prevailing winds here come from “Grid North”. They first encounter the “front” of the Elevated Station, then pass around / under it into the Operations Sector (“backyard”), where we have most of our logistics (storage, outbuildings, etc).

Windblown snow is carried toward the station. Some is deposited on the front side, some passes under or around.

The Elevated Station itself acts as a bit of a snow barrier – it’s designed to avoid any major drifting/accumulation, but there’s still a stark difference in elevation between the front and back.

The station was once significantly more elevated than it currently is. The snow is creeping up! This is apparent when you look at the stairwells down to “ground” level. The bottom of the stairwells are completely buried.

Part of the elevation difference between the front and the back is just the result of wind-blown snow interacting with the building.

However, in addition, a great deal of work is done to keep the backyard relatively flat / level. This prolongs its life at a given elevation, before we have to do all the hard work of lifting things up. We move tons of snow! It’s nearly a full-time job.

However, even in the operations sector, it’s still apparent that we’ve had significant snow accumulation over the decades.

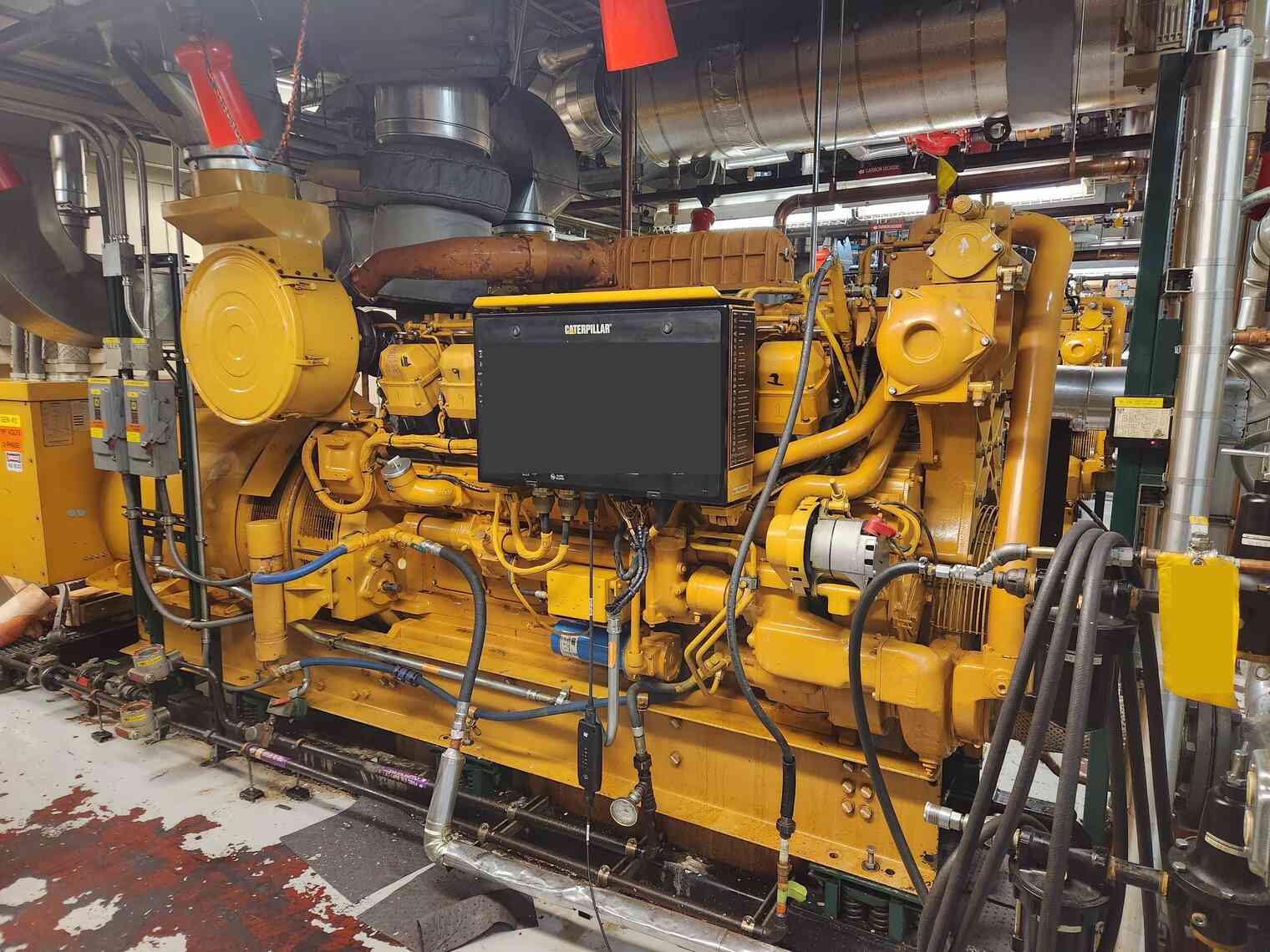

Most notable is the Arches. The Arches are a series of metal semi-circle storage/work facilities, built decades ago, well before the current modern Elevated Station. These are still in active use today! They house our power plant, water plant, primary cold/warm storage, fuel storage, carpenter shop, and vehicle maintenance facility.

They are also completely buried under decades of accumulated snow! We can walk right over them, and if it weren’t for the ventilation shafts and miscellaneous other utilities, we’d be none the wiser.

The power plant has also been here for decades. It’s been refurbished and overhauled over the years, but the building has been here for quite a long time. It’s now completely buried! All that is visible are the exhaust vents.

Getting down from the Elevated Station to the Arches means descending about 50ft. We’ve built a vertical tower with an enclosed staircase for this purpose. Only about half of it is visible here! The rest is underground.

Less stark but still telling, there are a number of buried infrastructure elements in the backyard.

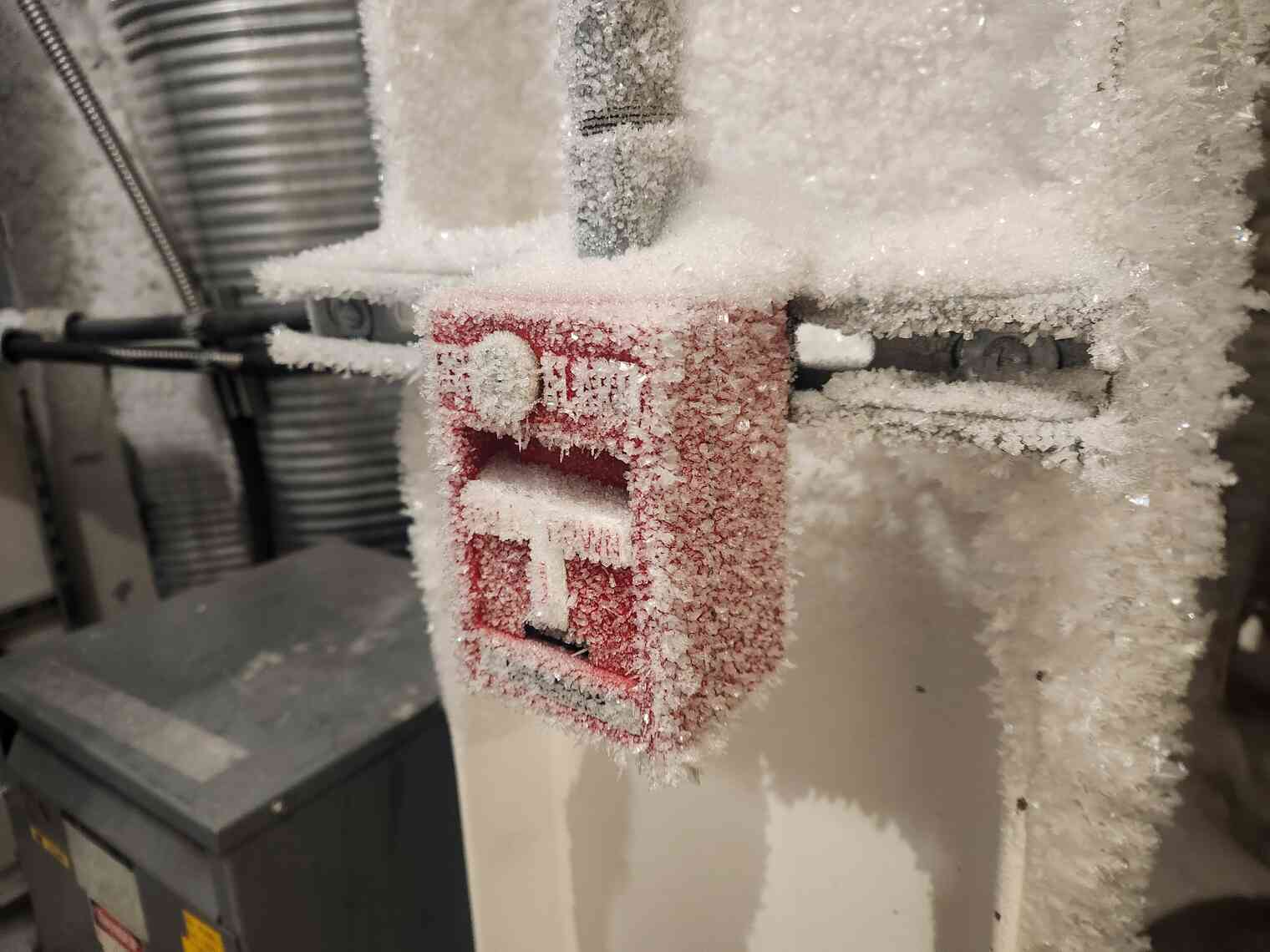

Here’s the access hatch to a buried infrastructure vault. Significant work goes into “digging out” things that have become buried, so they are still accessible. At some point, however, the snowcover becomes too much, and the hatch needs to be extended up to the current ground level.

There are examples all over station of extended hatches and ladders, to reach infrastructure that keeps getting buried deeper below ground level.

Here’s a work in progress at a location a bit farther out from station. A team has dug out a buried access hatch, and soon an extension will be added so that it sits at the new ground level. The infrastructure underground doesn’t change, but the access hatch requires constant maintenance.

In the backyard, there are a number of strategies to deal with the accumulation of snow.

Some buildings are built right at ground level. These will get slowly buried, unless work is done to engineer the snow around them. You can engineer away several feet of snow accumulation, and still make a building seem at “ground” level, just by introducing a gentle downward slope toward a building from the prevailing ground level.

Here’s a few buildings that are not elevated. Yes, they collect snowdrifts. And yes, they’ll eventually have to be moved! But for now, the herculean effort to grade and engineer the topography of the backyard means they are still accessible at “ground” level.

Speaking of snowdrifts, they are relentless! They will pile up against anything facing the wind. Here’s one ground-level outbuilding with some drifts up against it:

There is also a lot of ground-level storage. Here’s a typical storage aisle:

Other buildings are designed to be resilient to some amount of snow accumulation. Just like the main Elevated Station, here’s a building that is elevated above ground, so it can more gracefully tolerate a shift in ground level.

We also make use of elevated storage! Here’s a series of elevated storage platforms. This is more complex and more expensive than just putting stuff on the ground, but it means we’ll be able to access it for years to come without having to dig it out.

On a lighter note, one benefit of our massive snow hauling operation is that we can occasionally indulge in a bit of fun. Here’s the South Pole Sledding Hill, lovingly maintained by station staff. There’s plenty of snow to go around!

It’s neat to see the layered history of the South Pole. You can roughly gauge the age of infrastructure by how deeply buried it is!

Walking from the Elevated Station down to the Arches is a fun journey into the past.

Climbing down an access hatch, extended multiple times to keep up with the relentless snow, is a good day-to-day reminder of the forces of nature at work here.

I hope others find this as interesting as I do.

Until next time!